For HIV patients who struggle with daily pills — because they are homeless, or suffer from mental-health problems or drug addiction — long-acting injectable treatments are the newest innovation in HIV treatment and may offer hope, said Dr. Monica Gandhi on Tuesday’s Medical Grand Rounds talk at the University of California, San Francisco.

But the long-acting anti-retroviral treatment, given every four or eight weeks, has so far only been approved for those who have been taking daily oral pills and have a low level of HIV, Gandhi said.

That should change, she added.

HIV rates among homeless people, for example, are disproportionately high, meaning that the very populations who would most benefit from long-lasting treatments cannot currently take them.

“The minute the long-acting anti-retroviral therapies came out, we wanted to use them in patients who have a hard time taking therapies … ” she said. “We wanted to use them in our patients with homelessness.”

However, this injectable treatment has only been tested in trials with patients who have a very low level of HIV in the body and are already taking daily pills.

“But these aren’t our patients who have adherence problems,” Gandhi said.

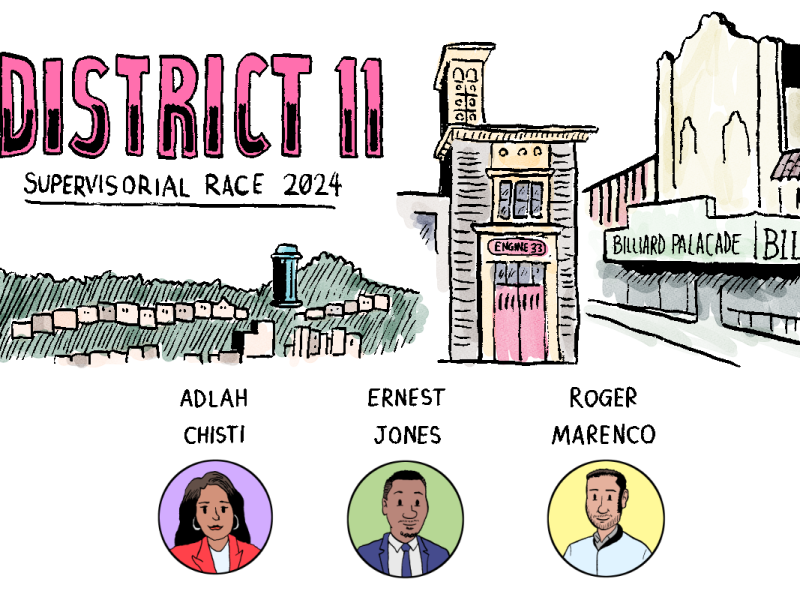

Last year, 157 people in San Francisco were newly diagnosed with HIV, an overall 12-percent decrease since 2019. But the decrease has slowed, compared to the 56-percent drop seen from 2013 to 2019, according to the 2022 HIV Epidemiology Annual Report from the Department of Public Health.

And, it is the more difficult-to-reach patients who are becoming infected.

People experiencing homelessness accounted for nearly one in five new HIV diagnoses. While HIV-related deaths continue to decline, 18 percent of deaths among people with HIV were from drug overdoses from 2018 to 2021, the report shows.

Also, for the first time, there were higher rates of new HIV infections in Latino men than in Black men in 2022. Infection rates for both groups were substantially higher than in white or Asian/Pacific Islander men.

Right now, the “first line of therapy” for those with HIV is anti-retroviral therapy in pill form. But this is not enough, said Gandhi, because it is difficult for some patient populations to take a pill every day.

Housing insecurity, substance use and mental health concerns are the three biggest barriers that keep people from sticking to a daily regimen, Gandhi said.

The best alternatives are injectable, long-acting, anti-retroviral therapies. Compared to daily pills, the injections can be administered either once a month, or once every two months in the case of a higher dose.

To address the gap, Gandhi and her team at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital enrolled 261 patients in a demonstration project. These included people who have unstable housing, mental illnesses and substance use disorders.

Early evidence from 133 of the study participants shows that long-acting anti-retroviral therapies work, even on patients who are not taking a daily pill or don’t have a low level of the virus. Those who started out with a low level remain at a suppressed level. For those who did not begin the study with viral suppression, the study showed a 90 percent viral suppression rate.

In the updated results of all 261 people, a viral suppression rate of 85 percent was reached among those who had a higher level of HIV when they started.

“We have a lot of positive feedback from people who’ve never been able to take oral [treatments], who are virologic-suppressed for the first time, and how positively motivating that feels,” said Gandhi, who argued for adding the long-acting treatment to the National Institutes of Health HIV guidelines to serve a broader group of patients.

Although leaders in the field have spoken up about including the long-acting anti-retroviral therapies in the national guidelines, the guidelines have not yet been changed.

Clinicians, however, can and do prescribe the injections for patients who have difficulty adhering to a daily pill, Gandhi said. But including them in the federal guidelines would expand the reach.